by Brian Prugh

Susan White, Joseph Patrick and others at Hudson River Gallery, on view over the summer.

While not grouped together as a themed show, the Hudson River Gallery is showing work from several artists that invite comparison. The work of Susan White and Joseph Patrick make a somewhat unlikely pairing: Patrick’s meticulous compositions of tarps strung up to form makeshift awnings are at some remove from White’s paint smears and biomorphic forms suspended from a delicate latticework of ultra-thin lines. Both however engage with line in a way that sets their work apart from some of the other work on view, and that reveals a remarkably similar approach to painting.

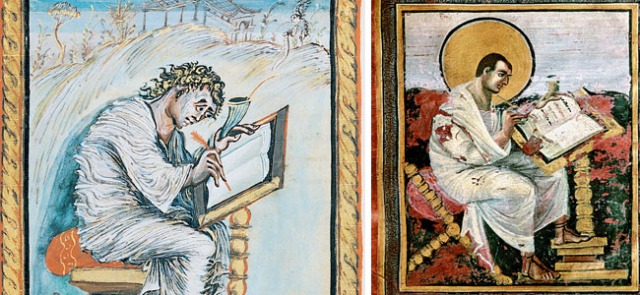

Detail of a “carpet page” and St. Matthew from the Lindisfarne Gospels, by Eadfrith, c. 700 AD.

Detail of a “carpet page” and St. Matthew from the Lindisfarne Gospels, by Eadfrith, c. 700 AD.

Before discussing Patrick and White’s use of line, it will be helpful to make a distinction between what I will call the “ordering” line, and what I will call the “line as mark.” I wish to call attention to the fact that these are two fundamentally different kinds of lines, and to make the case that the similarity between the work of White and Patrick consists in their use of the ordering line. Consider, for instance, the difference between a carpet page or St. Matthew from the Lindisfarne Gospels and St. Matthew from the Ebbo Gospels. The use of line in the Lindisfarne Gospels is everywhere after structure. In the carpet page, the linear elements loop and interlock to form a tangled mess of lines: but the mess is ordered, it is structured, and the repetitions and interlocking elements unite to form a coherent vision in which the drawn line functions as a building block and ordering principle. Similarly, on the St. Matthew page lines carefully trace and delineate folds of cloth, contours of figures, and the structure of the room, furniture and frame such that there is no line that does not provide information about the form of the drawn saint. Importantly, there is no “stray mark”—there is an incredible economy of line, with each serving a distinct and legible function.

Detail of St. Matthew from the ninth century Ebbo Gospels and St. Matthew from the Coronation Gospels, c. 800.

Detail of St. Matthew from the ninth century Ebbo Gospels and St. Matthew from the Coronation Gospels, c. 800.

By contrast, the lines of St. Matthew in the Ebbo Gospels mass together to create an energetic surface more like the solid forms that define the Coronation Gospels’ St. Matthew from a generation before than the careful and thoughtful delineations of the Lindisfarne St. Matthew. The “line as mark” works with the other marks to form areas of light, shadow, and differing colors out of which an image emerges. The position of each particular line is relative and inexact and is relevant only within the cumulative pile-up of lines. By contrast, the ordering line occupies a definite and distinct place in a linear matrix, identifying a particular form or force present in the composition.

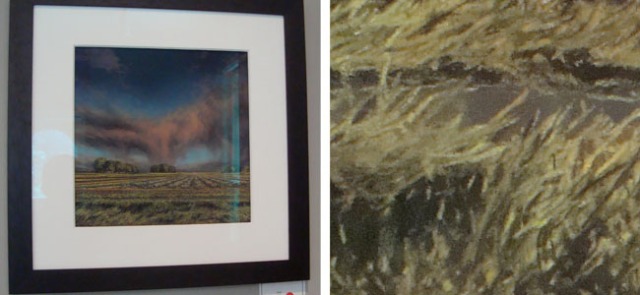

A pastel, with a detail of the bottom center, by Ellen Wagener. Photos by Brian Prugh.

A pastel, with a detail of the bottom center, by Ellen Wagener. Photos by Brian Prugh.

The distinction between the two kinds of line is evident in the current exhibition at Hudson River as well. In the pastels by Ellen Wagener and those by Roberta Williams, lines pile up in masses indicating the grasses, trees and crops that define the Iowa landscape. The lines create a visual texture appropriate to the vegetation. But these lines do not carefully attend to each blade of grass (such attention is precluded by the relationship between the scale of the landscape and the scale of the drawings) as some work by, for instance, Andrew Wyeth seems to: the lines are the mark through which the visual character of the landscape is communicated. They belong more properly to the texture of the work than its form, which is dominated by the horizon, sweeping areas of vegetation, and punctuated by trees.

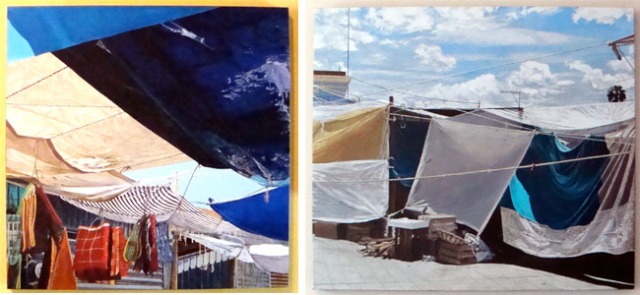

Lines in tension in two paintings by Joseph Patrick. Photos by Brian Prugh.

Lines in tension in two paintings by Joseph Patrick. Photos by Brian Prugh.

The use of line in Patrick’s paintings of tarps serves a fundamentally different function. The lines are literally holding the composition together. Should one of the ropes that define them snap, a tarp would fly or fall away—the balance of light and shadow would be interrupted, color relationships would change, the forms would collapse. The lines holding the tarps together could stand appropriately for man’s “blessed rage for order”: the taut rope is at once one of the most primitive and most precise means of ordering the world. The beauty of a sailing vessel’s stays and halyards or of the suspension cables on the Brooklyn Bridge are bound up in this ordering, structuring line. The line, as it appears in the painting, both shows off this structure and questions it. The tension between the hand-tied rope and the hand-drawn line frames the kind of wonder one feels in the contemplation of man-made objects: objects which, although they might possess a certain mystery, still promise to divulge their secrets because in an important way the minds of their makers are knowable. In Patrick’s canvases one is convinced that each rope painted in tension is doing something: the rope is visible evidence of human meddling in the world. These lines are poised against the planes formed by the tarps: they hold the tarps in tension, giving them form. The tarps, as anyone who has ever tried to set up a tent in the dark knows, resist form. They are all too happy to be reduced to a crumpled mess on the ground, to give way to the forces of wind and gravity. The human forces of tension applied against the natural forces of entropy are carefully charted in Patrick’s paintings—the angled lines, the curvature of the sloped tents, and the folds and drooping edges all articulate the tensions inherent in the situation, which Patrick translates convincingly to the canvas.

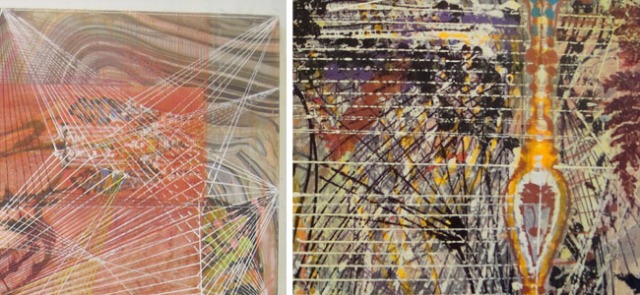

One can easily get tangled up in the webs of fine lines in White’s paintings, but the ordering principle behind them becomes clearer as one investigates the terminal points and structured intersections. Some detail views become helpful here.

Susan White, detail from a corner of “Rapture” (photo taken from Huson River’s web site) and detail of the center right of the painting pictured below, photo by Brian Prugh.

Susan White, detail from a corner of “Rapture” (photo taken from Huson River’s web site) and detail of the center right of the painting pictured below, photo by Brian Prugh.

The image on the left shows a suggestive detail of lines emanating from the corner of the painting—suggestive because it offers insight into the way that the layers of lines are generated. Beginning, perhaps, with explorations to and from certain critical points on the canvas (located either geometrically or by feeling), they pile up like a geometrical construction gone awry (as can be glimpsed in the figure on the right). A geometer, having completed such a construction, would despair of ever being able to re-create it. But once created, the intersections and the intervals created by the pile of lines define the proportions and placement of the blotted forms that are scattered about the canvas. The lines, importantly, amount to something. And they do not amount to something in the way that Wagoner’s lines amount to a field of grass: the lines do not draw the image as Wagoner’s do, they structure the image. White’s lines, as Patrick’s, identify the forces holding the image together. Where Patrick’s are tied to an external ordering principle, White’s reveal a constructing, making hand. The passages that I find most convincing, as in the painting on the left below, are those in which the grid not only sits below the image, defining relationships, but also cuts off and defines areas of paint from above, thus allowing the line to flicker between preliminary structure and facade.

Two Paintings by Susan White. Photos by Brian Prugh.

Two Paintings by Susan White. Photos by Brian Prugh.

I have belabored the formal character of the distinction between the “ordering line” and the “line as mark” in order to identify what I see to be a fundamentally different character between the two. The line as mark is a formal device—a technique—used to achieve a certain effect (to render the look of something, to capture something of its feel or energy). The ordering line, by contrast, is after a different end. It seeks to lay bare some truth (or it is the truth about the structure of the image lain bare). Where the line as mark seeks to transfer something onto the canvas (be it an object in the external world or something interior), the ordering line seeks understanding—it seeks to make connections. And while the line as mark can certainly be probing, I am inclined to call the ordering line “the questioning line,” because even as it defines an order and projects a structure onto the image, it remains responsive to that image and capable of refutation. The ordering line asks a question, and seeks an answer. The line as mark seeks, through a kind of pure visual poetry, to arrive at the answer directly—intuitively.